- Home

- Ingrid Ricks

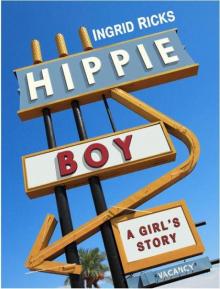

Hippie Boy: A Girl's Story Page 6

Hippie Boy: A Girl's Story Read online

Page 6

After feasting on a celebration dinner at a fancy restaurant nestled against the mountains in Provo, Utah, we would head back to the Osmond compound where a surprise would be waiting for me. My new parents would walk me into my bedroom—a big, beautiful room with delicate wallpaper featuring tiny purple violets and plush, cream-colored carpet. In the center of the room would be a large, four-post bed with princess curtains and a white, lace-lined down comforter. Amid my squeals of delight, Marie would come into the room, gently take me by the hand, and lead me to my walk-in closet, which would be packed with Calvin Klein jeans, thick, hand-knitted sweaters, and a dozen or so pairs of Cherokee-brand shoes.

My daydreams were so vivid they began crossing over into real life. I started making daily phone calls to an Osmond Ranch I had located in Paradise, Utah, hoping that Donny, Marie, or their youngest brother, Jimmy, would answer. I was so sure the Osmonds were coming for me that I sat glued to the Donny & Marie Show each week, and then headed down to the cellar where Mom stored our church-recommended food supply to mimic their songs. As the youngest and newest Osmond, I figured I would be joining the Donny and Marie act and I wanted to be prepared.

Connie, also an Osmond fan, was disgusted by my near perfect delivery of “Paper Roses,” Marie’s signature song.

“You know, you could get sued for copying her like that,” she bellowed once when she caught me mid-act. “They have copyright laws!”

I ignored her and kept singing. Inside, I was ecstatic. I knew I sounded good and her protests only confirmed it. When my family came for me, I would be ready.

CHAPTER 5

“INGRID! CONNIE! COME to the kitchen now!”

Dad’s angry, thundering voice triggered a panic button inside me.

My nine-year-old mind started spinning and racing through the past week, trying to remember what I had done wrong. Nothing was ringing a bell, but from the sound of his voice, I was sure we were in trouble.

“I said, ‘Come to the kitchen!’”

I raced to the room, fighting the urge to throw up. Connie, now twelve, came scurrying down the living room hallway and arrived at the same time. Our eyes locked for a second and I saw my fear mirrored in hers. We both turned toward Dad, who was pacing next to the table and looked like a lion ready to pounce.

“Go get your shoes on,” he ordered. “You two are doing the grocery shopping.”

For a second I felt relieved. Dad was angry, but he didn’t seem to be angry at us. Then the weight of his words sank in. He wanted Connie and me to do the grocery shopping.

Mom never allowed us to pick out food from the grocery store. She always planned our meals ahead of time from the Meals on a Budget recipe book she’d been given by one of the sisters at church. She made a detailed grocery list before leaving the house so she knew exactly what she needed and wouldn’t make an impulse buy that she would regret later.

I shot a nervous glance at Connie and then looked at Mom. She was sitting near the end of the kitchen table. The blood had drained from her face and I could see tears bubbling in her eyes. As soon as she saw me looking at her, she turned away.

Dad pulled a hundred dollar bill from his wallet and handed it to Connie.

“Here. This ought to cover it.”

I eyed the crisp, green bill Connie was now clutching and heard myself gasp. In my nine years, I had never seen that kind of money.

I looked at Mom for some sign of approval. Her lower lip was quivering.

“Jerry, you can’t let them do the grocery shopping. That money has to last us the entire month.” Her voice was quiet and pleading.

Dad didn’t respond. Instead, he turned back to Connie and me.

“I said to go get on your shoes. I’ll meet you both in the truck.”

I didn’t dare look back at Mom. We ran to our rooms, grabbed our shoes, and hurried outside.

It was only an eight-block drive to the grocery store, but it felt like an eternity. I was seated in the middle next to Dad and could feel his heat. I glanced at Connie, who was staring out the passenger window, pretending to be interested in the houses we passed.

I wanted to ask basic questions, such as “How much hamburger should we get?” and “Do you think it would cheer Mom up if we picked up some ice cream?” Instead, I concentrated on my hands, trying to force them with my mind to stop trembling.

Dad pulled into the grocery store parking lot and drove up to the glass doors.

“I’ll pick you up in a couple of hours,” he said.

We took this as our cue to get out. As soon as Connie slammed the truck door shut, Dad hit the gas and drove off.

I couldn’t get the image of Mom out of my head. I saw her sitting at the table, tears running down her cheeks. I could hear her pleading with Dad not to give us the grocery money.

I didn’t want to hurt Mom. But I didn’t dare defy Dad. I was scared. But Connie, who had recently started seventh grade, seemed perfectly fine. She flipped her feathered brown hair over her shoulder, marched through the automatic glass doors, and headed straight for the line of grocery carts. She grabbed one and motioned for me to do the same.

“We’ve got a lot of groceries to buy,” she explained patiently, as though she had done this a million times. “This way, we make sure we have plenty of room for everything.

“Don’t worry about it,” she added, seeing the panic on my face. “This is our opportunity to show Mom that we are responsible.”

She smiled and I immediately understood that there was a hidden meaning to her words. This was also our chance to get some food we liked.

I started to relax a little. Maybe Connie was right. Maybe we could do a good job and make Mom happy.

I followed her up the first aisle, helping her to scan the shelves for the no-name products like Mom always did. Connie told me the secret was to look for the ugly packaging and to check the bottom shelves, where she said most of the no-name brands were hidden.

“It’s all the same food,” she explained, acting like she had been to cooking school. “The only thing you’re paying for are the labels and fancy pictures.”

I didn’t know how Connie knew so much about food, but I was grateful that she was taking charge.

Truthfully, Connie and I didn’t really have that much in common anymore. Since starting junior high a couple of months before, she had joined the volleyball and basketball teams and was always at practice or at a game. And when she wasn’t doing that, she was hanging out with her pet rabbits or the animals at Willow Park, a small, nearby zoo. It was like she was turning into a jock or something—which was the complete opposite of the cheerleader I still envisioned becoming soon.

The first aisle was packed with deli meat and crackers, and aside from grabbing a large box of saltines, we skipped over everything there. The next row in was the cereal aisle. Here, Connie paused.

“I don’t know about you, but I’m ready to take a break from Cream of Wheat,” she said, a sly smile creeping across her face.

“Definitely,” I said, starting to get excited.

I moved my cart to one side of the aisle to get it out of the way and took my time scanning the wall of cereal boxes. My eyes first locked on a jumbo box of Fruit Loops. That’s what I really wanted. But I knew they were too expensive and that getting them would upset Mom. I also craved Cocoa Puffs, but I forced my eyes to pass on those too.

“How about something like Cheerios?” I offered finally.

“Good choice,” Connie said. We scanned the bottom shelf until we came across a two-pound plastic bag labeled Toasted Oats and tossed it into my basket.

The next aisle over, we picked out ten boxes of Hamburger Helper, and grabbed several bags of egg noodle pasta. We also stocked up on cans of no-name French beans, peas, and tomato sauce.

Now that I was in the swing of things, I was having fun and starting to feel confident about our grocery shopping abilities. I trailed behind Connie, carefully weaving my cart through each aisle, ignoring the quiz

zical looks from the moms we passed.

In the meat section, we selected three five-pound family packages of ground beef―23 percent fat because Connie pointed out that the higher the fat content, the cheaper the meat. At the dairy section, we picked out two eighteen-pack cartons of eggs. And in the vegetable section, we selected a head of iceberg lettuce and a twenty-pound bag of baking potatoes.

Then it was time for the frozen food section.

Our mouths watered as we eyed the ice cream and frozen pizzas, which we forced ourselves to pass. But when I spotted the pot pies, my favorite food, I stopped.

“I think we should get these,” I said to Connie, preparing to argue my case. “I mean, each of them is a meal by themselves and they are easy to make.”

I loved pot pies—especially chicken pot pies. Once or twice a year, Mom surprised us with them. I loved that they were each in their individual packages, which meant that we could eat them directly from the tin. I also loved the thick, creamy broth, the chucks of chicken, and the way the peas and carrots tasted like the broth itself. But the best part was the pie crust. I was always careful to save the crust for last. I would make a small hole in the top of the pot pie, just big enough for my spoon, and eat out all of the broth, chicken, and vegetables. Then I slowly ate the crust, letting it melt in my mouth. Just thinking about it made my stomach growl.

“Please, Connie,” I continued. “They’re so good and they don’t use up any dishes, which means cleaning the kitchen will be easy on the nights we eat these.”

It didn’t take much convincing. We pulled out twelve of them, ensuring we had enough for two dinners. We also decided that a large bag of tater tots made good dinner sense and tossed those into the basket.

On Connie’s advice, we skipped the bread aisle because just across the parking lot was a Wonder Bread Outlet. It’s where grocery stores took bread that couldn’t be sold because the loaves had been squished or had exceeded the expiration date stamped on the bottom of the bag. But they were always at least half off the regular price.

The check-out clerk eyed us suspiciously as she rang up our groceries but she didn’t say anything—even when Connie handed her the hundred dollar bill. She returned a five dollar bill and change to Connie, who tucked the money into her front pocket. Then the two of us walked our carts jammed with food over to the Wonder Bread store and pushed them just inside the shop, where we could keep an eye on them.

I followed Connie to the bread section that covered the back wall.

“Look, Ingrid,” she said, motioning to the sign by the bread. “Ten loaves for one dollar! Mom is going to LOVE this.”

All of the ten-cent loaves were at least a week over their expiration date. We picked through them carefully, leaving behind the ones that felt hard and stale when we cupped the bags with our hands. We decided to go for all ten loaves, figuring Mom could store some of them in the deep freezer we kept on the back porch. Satisfied that this buy alone would put a smile on Mom’s face, we headed for the checkout counter. On the way, we passed by the fruit pies.

“I think we earned one of these, don’t you?” Connie said with a smile. I nodded and we quickly added two cherry fruit pies to the basket.

Connie paid for the bread and fruit pies with the five dollar bill left over from the main grocery excursion, ignoring the checkout clerk when she suggested that our mom wouldn’t want us bringing home stale bread. Then we added the loaves of bread to our stuffed shopping carts and headed back across the parking lot to wait for Dad.

We sat down on the curb and sank our teeth into our fruit pies.

“Now aren’t you glad that Dad asked us to do the shopping?” Connie asked as we slowly savored our fruit pies.

Dad’s Dodge pulled up soon after we had finished.

He stepped out of the truck to help us load the groceries. I was relieved to see a smile on his face.

“Well, look at this,” he said, eyeing the two carts filled with grocery bags. “It looks like you girls did just fine. I knew you would. Your mother’s always talking about the need for faith. Maybe she just needs to have a little more faith in you.”

We pulled up to the house and Dad unloaded the bags from the truck.

Then he drove off and left Connie and me to haul in the grocery bags ourselves.

My stomach was back to knots as I trailed Connie into the house with two bags of groceries, placed them on the kitchen table like Mom always did, then returned to the lawn to grab some more bags.

Mom came out of her bedroom to see what the commotion was. Her eyes were red and swollen.

I was so nervous I was ready to throw up the cherry fruit pie I’d just devoured.

“I tried to pick out the same kind of food you usually get and made sure we bought all no-name brands,” Connie said in a calm, upbeat voice. “And I think you are going are really love the bread deal we found. Ten loaves for only one dollar.

“Do you want to see what we got?”

“Not right now,” Mom said quietly.

She left the kitchen and went back to her bedroom.

I stared anxiously at Connie, who still seemed calm and in control.

“Don’t worry about it,” she said in a soothing, assured tone. “Mom’s still upset but everything will be fine. Let’s surprise her by putting everything away.”

A COUPLE OF MONTHS later, Mom called us all into her bedroom for what she said was a “big surprise.”

I was excited. Maybe she would say we were moving again. Or tell us that we were finally going to get a dishwasher. I entered the room and found her sitting on the worn gold bedspread that covered her bed, wearing a goofy smile on her face. She looked so happy she was glowing.

We all crowded around her, anxious to hear her announcement.

“Well, children. I’ve got some exciting news.” She paused for a moment to let her words sink in. The room was so silent I could hear my heart beating.

“I’m pregnant.”

If my siblings responded, I didn’t hear them. I was so shocked by Mom’s words I couldn’t focus.

This was definitely not the surprise I had in mind.

Her two-word announcement washed over me, and then began seeping in through every pore. She was having another baby. This meant another kid to take care of, another mouth to feed, another person to share what little we had.

“What are you thinking?” I wanted to scream. “You don’t even have enough money to take care of the kids you’ve got!”

Was I the only person who had any sense around here?

Every week I watched Mom as she sat down to pay the bills and felt her stress as she tried to determine which bills to skip. Dad’s deal with Mom was that he would wire her one thousand dollars a month, which rarely happened. But even when he was able to meet his commitment, there was never enough money to go around. Before anything else, Mom gave her ten percent tithing to the church, figuring that if she paid God first, God would take care of her. This left her with nine hundred dollars to work with for the month—when she was lucky. Each week, she took out her recipe box where she stored the bills and spread the papers out over our fold-out kitchen table. The one bill she always paid was our eighty-seven dollar mortgage payment because she wanted to make sure that we didn’t lose our house. From there, it was a crapshoot. If it was winter, she made sure she paid the gas bill so that we had heat, but sometimes the electricity got turned off. Aside of the hassle of going without our stove and washing machine, I didn’t mind this so much because we got to use flashlights and candles. But it was a pain in the summertime because that’s when Mom was likely to skip the gas bill—which meant we had to heat water in a big pot on the stove whenever we wanted to wash up.

The phone was always the first thing to go because Dad often ran up huge long distance bills during his visits home. Once, Mom got so fed up with him for always causing her to get the phone disconnected that she had a pay phone installed in the foyer leading to the living room. Then she secretly hooked up a

regular phone in her sewing room and kept it hidden in the closet.

“Don’t tell your dad about it or we’ll lose it,” she warned us.

When Dad arrived home, walked in the house, and saw the payphone, he came unglued.

“What the hell is this?” he yelled.

“We couldn’t afford a phone anymore because of your calls, so our only choice was to put in a payphone or not have a phone at all,” Mom answered smugly.

Dad dropped his bags in the hall, stormed back out of the house, and headed to the grocery store for a roll of quarters. When he came back, he pulled a kitchen chair next to the pay phone and began making his calls.

He used the payphone until that evening, when he heard the regular phone ringing from the sewing room closet. I was scared he was going to blow up, but he remained surprisingly calm.

“You know, I think your mother’s a little sick in the head,” he announced with a sigh. Then he took the phone out of the closet and started dialing. After that, the pay phone was useless so Mom had it removed.

I was tired of worrying about how Mom was going to take care of us. It was stressful and embarrassing. When our toilet broke, we spent nearly three weeks peeing in our backyard garden and knocking on our neighbor’s door when we needed to do a number two before Mom was able to pull together the money to hire a plumber. We never got to buy new clothes. They were either all hand-me-downs from my cousin or second-hand clothes from the church thrift store. And every week at school, I had to go through the humiliation of being called up to my teacher’s desk to get my free lunch tickets.

“Who is having hot lunch this week?” she would ask the class each Monday morning, counting the raised hands so she could get a tally for the lunch room cooks.

Then she would pull out two white envelopes from her desk.

“Ingrid and Nanette, here you go,” she would say.

Hippie Boy: A Girl's Story

Hippie Boy: A Girl's Story